“Native American societies have a lived sense of the unity of all living things, as expressed in the Native American phrase ‘all my relations,’ which has been called a prayer and a cosmology in one breath.”

Dr. Leslie Gray, Native American Psychologist & Shamanic Therapist, founder of Woodfish Institute

In 2019, I published an academic paper that went viral, prompting a shift in the narrative around our shared climate crisis. In “Climate Trauma: Towards a New Taxonomy of Trauma,” I pointed to the elephant in the room: we humans (along with elephants themselves) have now begun experiencing the effects of a new form of collective trauma that is superordinate to all the previously recognized forms of trauma; namely, the grievous wounding of a living planet that is not apart from us at any level. While I did not invent the term “climate trauma,” since my paper was generously made available online from the outset by its publisher, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., it has been widely shared in academic, psychotherapeutic, and activist circles, and the terminology has become a more honest and accepted way of describing the increasing psychological distress caused by the mortal wounds Western civilization is inflicting of the planet.

We tend to forget that “climate change” is just a scientific term used for measuring the effects humans are having on a living planet. It is a measure of an unnatural phenomenon, in other words – not the phenomenon itself.

That unnatural phenomenon is the ongoing wounding of a living meta-organism, Gaia, an inconvenient truth we prefer to avoid with banal euphemisms like ‘climate change’ and ‘global warming.’ Climate trauma, by contrast, is a psycho-physical term that more accurately describes the pervasive effects that this wounding is having on the biosphere. Since there is no more separation between body and mind than there is between humans and Gaia, those effects can be described at both a physical and a psychological level. We along with all other forms of life are Gaia, part of her self-regulating nature, and so of course her pain is our own. Unless we are disembodied by our sociocultural conditioning, as for example with toxic masculinity or patriarchal subjugation, we can now feel the force of that biospheric trauma. It has become endemic to us as a species.

So what does it mean to have named the drunken elephant in the global room of climate disruption? Acknowledgment of trauma, after all, is simply the first necessary step in recovery.

First and foremost, it means that this is a problem of relationship. That is, the existential conundrum that we know dismissively as global warming arose in our own relationship to a living planet. Thus, it can not be solved without addressing the relational issues that gave rise to it.

Second, and not to be glossed over in any way, to say that climate trauma is “superordinate” to cultural, epigenetic (generational), and individual trauma, owing to its pervasive scope and constant presence, means that all of our other unresolved relational traumas are always being triggered by climate trauma. And since all traumas are cumulative, the accelerating force of climate trauma is producing a kind of social and cultural “traumasphere” that is unlike anything we’ve previously experienced. If we are to be honest with ourselves, we are collectively on the verge of a mental and emotional breakdown that happens to reflect the accelerating ecological breakdown.

It doesn’t serve us to treat these phenomena as unrelated. The ongoing grievous wounding of Gaia – our life source and the source of all life – creates a feedback loop by which we are called upon to acknowledge and re-solve the underlying residual traumas of patriarchy, or the subjugation of the feminine (including Nature), genocide of the first peoples, who’ve always lived in close relationship with Gaia, and the trauma of white supremacy, which justifies the continuing subjugation and exploitation of the Global South by the Industrialized North.

These can seem like unrelated traumas at first blush. But when we ask ourselves why they are all being triggered at the same time, giving rise to the compelling social movements of MeToo, Black Lives Matter, and Indigenous Rising, we can see quite clearly how these are interdependent and interpenetrating traumas, how entangled they are with one another and with the climate crisis itself, and how the oppression at the root of these intergenerational traumas is fueling the extinction of life on Earth.

Is it really just a coincidence that the same segment of the population here in the U.S. that denies the existential threat of climate trauma has been forced to deny truth itself, propping up alternate facts, and has rather quickly come to embody an existential threat to democracy itself?

That is how trauma works. If we do not acknowledge it, then we are doomed to embody it. We become disembodied to ourselves and to the political corpus. We act out irrationally and emotionally, as if our very lives are being threatened by something as innocuous as a mask or a vaccination, and take comfort in fictions like building a large wall will somehow keep us safe.

It’s not unlike what Joseph Campbell said about myths: if we do not live our myth, our myth will live us. We cannot hope to collectively resolve climate trauma if we remain unwilling to acknowledge climate trauma in all its guises, because to act it out collectively based on repression and oppression promises only social and ecological suicide. Collective acknowledgment of climate trauma requires a more informed media and, yes, more honest politicians. As Greta Thunberg, the Sunrise Movement and Extinction Rebellion say, tell the truth.

As Naomi Klein first intuited, “this changes everything,” because everything must change if we are to re-solve our shared existential crisis. Which admittedly seems like a tall order. At the same time, we no longer have any realistic choice in the matter. As the poet Michael Robbins recently characterized our predicament in Harper’s Magazine:

“The world is always ending, but now it has ended.

No doubt it will go on having ended for some time.”

That is, ”…the world is always ending. But it has never before had such force… [L]ook at the world, what is left of it.” This is an apt expression of climate trauma.

To say that everything must change means that we must change, too. Every one of us. In our hearts, first, then in our thinking and, finally, in all our relations. Simply put, we must learn to really see ourselves as relational beings before we can set about repairing all our relations. This will not happen overnight, but it can and it must happen. Anyone who works on these issues long enough senses that a global shift in consciousness is already underway. The sooner it reaches critical mass, the more species and humans will survive the perilous future we now face.

To learn to see ourselves ultimately in relationship with Earth, above all, and from that expansive vantage point to meaningfully gauge our subordinate relations to bioregions, ecosystems, cultures, communities, families, and to self is to become indigenous to Earth. This is how we can systematically heal our existential trauma ~ by cultivating our own indigeneity, in community.

Why is the emergence of this post-modern indigenous culture so critical?

Listen to this beautiful summation from the United Nations:

Although Indigenous Peoples constitute less than 5% of the world’s population, they safeguard 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity, thereby playing a key role in climate protection. Indigenous peoples often have a spiritual connection to nature, which ensures that they take the protection of their habitat seriously.

***

With only a limited window of time to bend the emissions curve, adapting to changing climate conditions, and halt the rapid decline in biodiversity, the values and wisdom of indigenous peoples can help societies achieve this transformation… Such common values include Indigenous Peoples’ holistic view of and symbiotic relationship with Mother Earth – a relationship in which life thrives on the recognition of an inalienable interconnectedness and delicate balance.

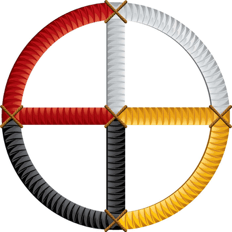

Like the Lakota notion of the “good red road,” amplifying our own indigeneity represents the most effective pathway for non-Indigenous people to come into proper relationship with Indigenous people – as opposed to reducing them to totems and fetishizing their Indigenous wisdom – and with our common life source. This is precisely what it will take to restore any kind of ecological balance in the Anthropogenic Era. Climate trauma arises in relationship, after all, and discovering our own indigeneity is responsive to both the existential crisis we face and the spiritual crisis that brought it about.

This postmodern take on indigeneity isn’t some new phenomenon so much as it is a new way of thinking about what we know is already working, and thus bringing into coherence the numerous strands of the global reformation that are already emerging from those of us who hear the cries of the world and feel Gaia’s trauma in our gut. Not only are we called by Gaia to this sacred task, Indigenous peoples themselves are calling us home in this way, as faithfully set forth by the Canadian writer/activist Peggi Eyers:

“As members of Earth Community, it is the birthright of the entire human family to be indigenous to the Earth, to appreciate and love the natural world, and to find our ‘indigenous place within’… By returning to our earth-rooted belief systems, and ‘reintegrating ourselves with our indigenous selves, we simultaneously reintegrate ourselves with the rest of humanity’ (Ward Churchill).”

(Exerpted from First Nations on Ancestral Connection, Stone Circle Press)

This resurrection of our Human Nature from the ashes of Industrial Civilization necessarily begins with the collective moral imperative of radical humility,due to the vast scale of our accumulated mischiefs. As the Austrian mystic Thomas Hubl says, “humility is born of our strength to be vulnerable.” Facing into the storm of climate disruption requires us to disown the hubris by which we’ve always assumed that we know better than Nature, and embracing the idea that we must now learn to serve Nature, seeing ourselves as part of and subordinate to Nature.

Any indigenous reformation of Western Civilization must also be anchored in a collective, sincere, and publicly expressed contrition over the ruthless genocide our progenitors have perpetrated on the inhabitants of the Americas. The ultimate humility implicit in the U.N. quote above is an acknowledgment by settlers and colonialists that Indigenous wisdom is superior to our own – that they’ve been right all along, and that we were wrong to see our life source as a ‘natural resource’ to be endlessly exploited. Water really is life, not a commodity. Nature really is sacred, and not something evil to wage war against – a damaging superstition Western Europeans religiously believed in when they invaded the Americas, and have only recently (mostly) given up.

Indian Americans are still 4 million strong here in the U.S., 50 million in Latin America, and we still owe them a fair accounting for the broken treaties and the perpetuation of intolerable economic conditions on many Native American Reservations today. As Fernando Pairicán, a Mapuche historian at the University of Santiago, states:

“For every act of genocide, there needs to be economic, political and social reparation. Only then can we move towards self-determination, equality and the restitution of lands to Indigenous peoples across the Americas.”

These kinds of truth and reconciliation processes, such as that put forward by U.S. Rep. Barbara Lee, are how we show that we are grownups capable of dealing with an existential crisis. By learning to see our Indigenous brothers and sisters as our spiritual elders on this relational path, by becoming their political allies as they throw off the societal chains of colonialism and oppression, and by soliciting their assistance in seeking out Gaia as our ally and not our enemy in the climate crisis, we can reconcile our shared traumas together, and redirect the energy liberated in that collective healing process towards climate recovery.

Together, we can return salmon en masse to the mountains and rivers where they have always spawned, we can return bison, prairie dogs and sage grouse to the desiccated grasslands of the plains states, drawing down more carbon in the process than we currently emit, and we can return beavers and other keystone species to our forests, restoring a proper balance between water retention and regenerative wildfire. Working together, hand-in-hand with tribal scientists and wisdom keepers, we can make amends for our recent past, learn to come into proper relationship with ‘Turtle Island,’ and even return key landscapes under stewardship arrangements with those tribes that we clearly wronged.

In a society and culture where we’ve become so disembodied and disconnected from the natural world and our own true nature, and at a critical time when so many are still reflexively dissociating from climate trauma, regenerating and cultivating a new kind of indigeneity, one that emerges naturally from our growing sense of shared responsibility for the climate, for our bioregions, and for our locally inhabited ecosystems, represents the missing piece, and the social glue, in the global puzzle of climate reconciliation and recovery. Restoring all our relations by embracing core Indigenous values like reciprocity, biophilia, and simplicity is not just the right thing to do morally – it is also, as a matter of science, the only way that we can compensate for our unconscionable procrastination in decarbonizing our economies, and thus in time reverse global warming.

And when it comes to drawing down CO2 from the atmosphere, ecology trumps technology:

“The cheapest, most effective way to suck greenhouse gases out of the atmosphere is to rely on nature. Nature does this for free. Trees, coral reefs and the ocean itself are much better vehicles for removing greenhouse gases than anything engineers have ever invented. And it doesn’t cost us anything, except to protect it.“

This according to Eric Dinerstein, one of the architects of the ambitious Global Deal for Nature first announced in the journal Science Advances in 2019 by an international team of scientists, now serving as the basis for negotiating the new International Biodiversity Conventions. As Newsweek’s science reporter Aristros Georgiou summarizes it, their proposal “aims to help ensure that climate targets are met while also conserving the Earth’s species.”

In support of this regenerative approach to climate and species recovery, the G20 recently agreed to fund and implement a “UNESCO Earth Network” education initiative that will place scientific experts into every ecosystem, eventually, in order “to sensitize and train 100% of the world’s population to environmental challenges, so that each individual is able to become a guardian of our Earth.” According to UNESCO Director-General Audrey Azoulay, the purpose of this ambitious program is nothing less than “to rethink our relationship with nature.”

That is how we cure climate trauma. And that is the emerging indigeneity that will see us through this crisis, transmuting our species in the process. As the Indian scientist and regenerative activist Dr. Vandana Shiva says:

“All of us are indigenous members of Earth Community equally – there is no higher placement of a master over another – and it is high time for all of us to become Indigenous again.”

1 Comment